I have to let the images speak for themselves in this one. For the most part.

Pretend that there is a world in which a line of leading questions, even aggressive questions, could be neutral. Such is the imaginary world of journalists.

The danger is playing the role of ‘the condescending coastal elite’. The heartland’s bugbear whose shadow is impossible to escape unless I somehow change my accent, gut my vocabulary, and cut off my hair.

Just look into it yourself. My limited opinion is that all art students should make a field trip here.

I wouldn’t have cared, and there wouldn’t have been anything to write, had there been a bit more clarification between whether or not Redlin was an ‘illustrator’ (as listed on Google), or an artist to the tune of ‘America’s Most Popular Artist’ (as listed by U.S. Art magazine nine years in a row, the entire duration of its polling activity). And further, what that distinction is good for (if anything).

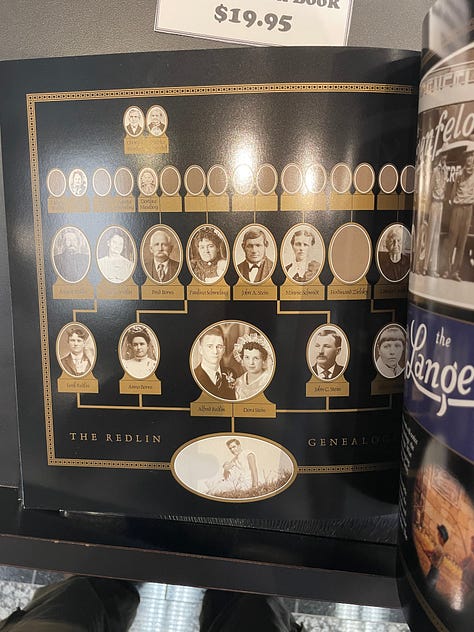

Really the only thing that matters is that Redlin achieved hometown hero status, which makes him at once less than a prophet and the envy of any young artist striving for a break. Not to mention an incredible amount of money.

But the questions I think need answering at some point:

Is there, or is there not an ethical aspect inherent to aesthetic categories as such? (Ie. the Beauty = Goodness equation of the Hellenist world). If it is the case, kitsch could be accused of deception, and—I don’t know… what?—round up all the ‘evil’ objects and burn them?

Is that the meaning of ‘Christo-Fascism’? How about ‘LGB-Fascism’? Doesn’t feel very good does it?

Alternatively: How much of the Redlin brand is a consequence of the amputation of his leg as a teen? From one crip to another: bro just wants a hug.

Then again there’s the thing about staying silent where one cannot speak.

Donna, the uniformed receptionist inside the heavy gold-clad front doors, receives my initial curiosity quite affably until after I look around, take my pictures, and say goodbye. I turn around in the parking lot half-way to the car for the sake of one crucial data point I forgot to ask about. Again I pass through the middle of the eight monolithic cold pillars thinking I am completely in my right mind. To Donna, who looks much more serious than the first time I walked in, I ask how many visitors on average the Art Center receives annually, which I take as pertinent to the institution’s stated touristic goals, which are not at all veiled in any of the public material.

“Hmm, I don’t know,” she replies then adds—likely making a value judgement based on my answer to her procedural question earlier about where I come from—her eyelids narrow ever so slightly: “Why are you here?”